Challenges

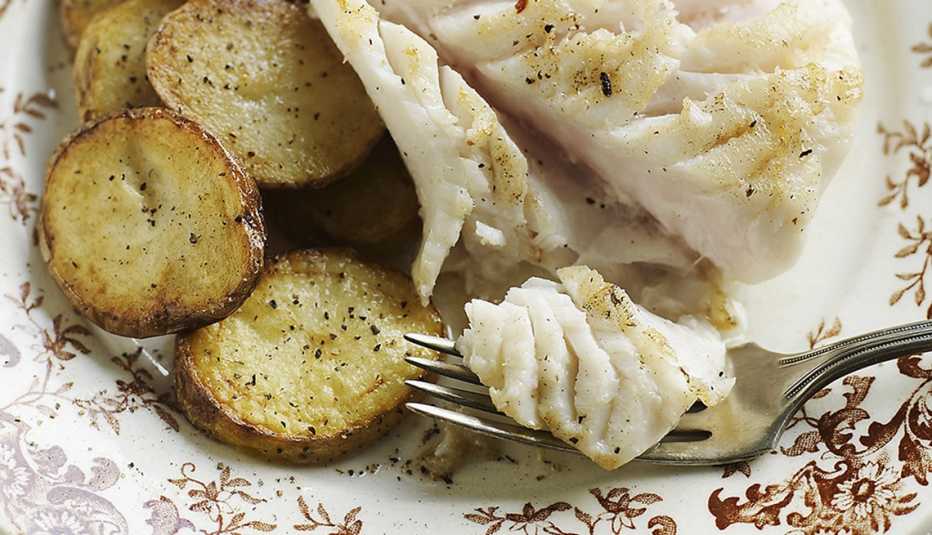

When you’re thinking about what to have for dinner, think about the classic card game Go Fish. A staple of brain-friendly diets like the Mediterranean Diet and the MIND Diet, fish supports brain health in several ways, which is why AARP’s Global Council on Brain Health recommends eating fish that is not fried at least once a week in its 2018 report Brain Food.

Eating fish regularly could help keep your mind sharp as you age, research shows. In a meta-analysis of 35 observational studies involving more than 849,000 total participants over age 50, people who ate the most fish had an 18 percent lower risk of cognitive impairment than those who ate the least. The results, published in Aging Clinical and Experimental Research in 2024, found that eating about five ounces of fish per day offered the most protection.

When you tuck into a seared salmon filet or a spicy tuna wrap, your brain gets a healthy dose of omega-3 fatty acids. People with high blood levels of omega-3s performed better on memory and processing tests and had greater brain volume (measured using magnetic resonance imaging, or MRI) in a study of 40 cognitively normal adults with a mean age of 76 published in Brain Sciences in 2023. According to the study’s authors, omega-3s may help promote brain health by lowering inflammation, slowing the loss of white matter (the part of the brain where the fibers that reach out from neurons communicate and exchange information), improving neuron function and reducing the abnormal buildup of proteins associated with Alzheimer’s disease.

Feeling inspired to eat more fish? Baked, broiled or even air-fried are great, healthy options. Get started with our recipes for fish tostadas with chili-lime cream, Parmesan-crusted cod with tartar sauce, garlic roasted salmon and Brussels sprouts and Thai sole and vegetables.

More From Staying Sharp

These 4 Foods Could Be Harming Your Microbiome

Explore the connection between your food and your gut health and explore healthier choices

7-Day Mediterranean Diet Meal Plan to Help Support Brain Health

Enjoy a week of delicious meals in this 7-day brain-healthy meal plan

The Best Way to Store Fruits and Veggies

Learn how to store your produce